Hubertus Knabe is a German historian who has written extensively about Communist East Germany (GDR) and the character of its dictatorship. In addition to his books and articles, he contributes online commentary in his E-Letter. This text is a translation of his E-Letter 160.

The short essay provides a critical evaluation of the current German discussion around the status of May 8, the date of Germany’s formal surrender in 1945, what became known in the United States as Victory in Europe Day (V-E Day). How should this momentous date be commemorated? How has its status changed over time? These are questions about memory but also about important political questions of the present, and not only in Germany.

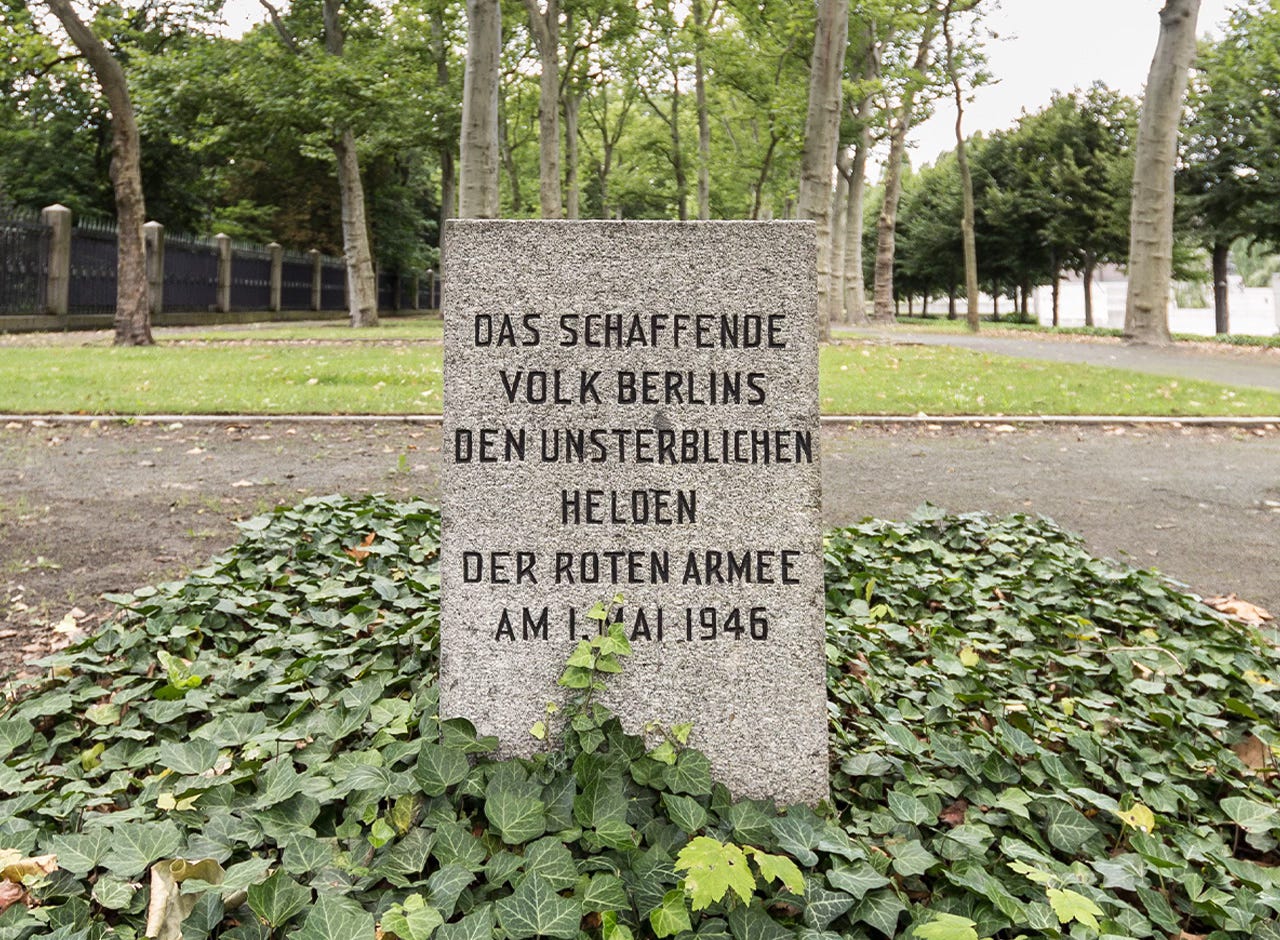

Knabe traces the divergent interpretations of May 8 in East and West Germany. In the Communist East, the date was quickly assimilated into a partisan ideological narrative, according to which the Soviet Red Army “liberated” Germany—liberated rather than defeated. That claim of liberation served to celebrate the dominant role of Russia in the countries that would end up trapped behind the Iron Curtain. It also supported the fiction that Communist East Germany represented an authentic expression of an indigenous “anti-fascist” movement. As Knabe points out, all that was false: as it fought its way across Europe, the Soviet military leadership never talked about freeing Germany—its expressed goal was to crush its army and to destroy the Nazi regime. Nor did most Germans alive at the end of the war experience May 8 as a liberation: the Allies’ victory was an unambiguous defeat for the German state, to which most Germans remained loyal until the end. The exceptions for whom May 8 genuinely brought liberation were groups like Jews and others who had survived the camps or in hiding or foreign workers who had been enslaved by the Nazis.

Knabe also traces the transformation of May 8 initially in West Germany and, after 1989, into the self-understanding of unified Germany. While the ethos of the early decades in the West had none of the “liberation” rhetoric typical of the East, it gained ground in the discussions in 2025, the eightieth anniversary. To explain this shift—from May 8 as defeat to May 8 as liberation—one might point to the fading of any immediate historical memory of the end of the war, which had not been understood as liberation by most of those who lived through it. Alternatively, one might attribute this shift in interpretation of the date to the influence of politicians or activists from the former East, now shaping the cultural hegemony in the Berlin republic. That hypothesis of a GDR or post-GDR factor driving culture in unified German is an ongoing topic for Knabe. In any case, one could anticipate a competition between two alternative explanations of the cultural shift from a narrative of defeat to a narrative of liberation: it can be viewed as an endogenous development within (West) German culture or alternatively as the result of exogenous influence from the former East. Historians of Germany can work that through.

All of this is important for students of German history. Yet Knabe’s E-Letter also has several resonances of wider import, beyond Germany, with regard to the character of cultural developments across the developed world. Germany is of course a particular case with its distinctive history and experience of modernization, its “Sonderweg.” Yet Germany is also a modern Western democracy, where cultural and political developments can shed light on what is transpiring elsewhere in Europe or the United States. What has been happening in Germany in terms of cultural tendencies is not only German.

First and perhaps most evidently, Knabe’s E-Letter points to the importance of looking with skepticism at the phenomenon of those protest movements, including in the United States, that call themselves “antifa.” What is the meaning of that appellation? Of course, the several fascist dictatorships—and in this context, that includes the Nazi regime as well as Mussolini’s Italy and others—faced politically heterogeneous opposition in the pre-war period from anarchists, socialists, and democrats, and not at all only from Communists. In fact, some Communists found themselves compelled to repress their own antifascism during the period of the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939–41 (Communists are not reliably antifascist). Today those historical fascist dictatorships are long gone, but they continue to deserve retrospective condemnation and criticism. In that sense, antifascism is an unquestionably appropriate stance.

Yet the validity of antifascist critique has been tarnished because the discourse of “antifascism” became the hegemonic ideology in the Soviet-dominated Communist movements, especially but not only in East Germany. The heterogeneous antifascism of the pre-war era faced extensive repression by Communists during and after the war. In other words, “antifascism” is not only an abstract name for opposition to Hitler and Mussolini; it also became the specific legitimating ideology of Communist dictatorships. Soviet Russian imperialism in Central Europe masqueraded as an antifascism that claimed to have offered “liberation,” but in fact crushed popular revolts: 1953 in East Germany, 1956 in Hungary, 1968 in Czechoslovakia. Dissidents were imprisoned or executed in the name of “antifascism.” In the same vein, the Berlin Wall was labeled the “antifascist protective wall.” The rhetoric of “antifascism” historically was used repeatedly to justify oppression.

To what extent do contemporary “antifa” movements embrace that repressive legacy? Are they historically and politically aware of the implications of the rhetoric of “antifascism” in dictatorships, or are they simply ignorant of the past? To answer that question would require extensive empirical research, as well as an evaluation of the shifting semantics around the term. In general, however, in much of the Western left there has not yet been a sincere reckoning with the experience of Communism in Central Europe. In Germany, the Left Party and its twin, the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, act to maintain positive memories of East German socialism.

Part of the complications around May 8 and antifascism has to do with the historical abandonment of the anti-totalitarian consensus of the Cold War, which once condemned both Nazis and Communists: both extremes on right and left used to be deemed dangerous. In the meantime, a new stance has developed, especially in intellectual and academic circles, which is hostile to Nazis and fascists but increasingly tolerant toward Communists, past and present. For them Nazism represents, understandably enough, absolute evil, but Communism is valued as a good idea that was perhaps just poorly implemented. Why not try it again?

This transformed political perspective, with its opening to the radical left, becomes even murkier when antisemitism is factored in. “Antifa” draws its aura of heroism from its animosity to Nazis, the perpetrators of the Shoah. But the Communism, of which many—but not all—of today’s antifa adherents are fond, pursued its own Jew-hatred in the form of Soviet anti-Zionism. Moreover, when antifa demonstrates for the destruction of Israel, it operates in a direct continuity with Nazi hostility to Jews, including Jews who had settled in the British Mandate. The Nazi source of anti-Zionism is embodied in the person of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin el-Husseini, the founder of Palestinian anti-Zionism who consorted with Hitler and spent World War II broadcasting antisemitic propaganda from Berlin. Antifa claims, in other words, to be anti-Nazi even as it advocates Nazi policy. The ideological tangle here is sufficiently confusing to warrant caution toward the hopelessly tainted lexicon of “antifascism.”

To regret the abandonment of the anti-totalitarian consensus that condemned both Nazism and Stalinism does not at all mean that they were identical or equivalent. Both forms of totalitarian rule committed massive crimes, but the two regimes displayed empirical differences. Exterminationist antisemitism was central to Nazism, leading to the Shoah. The deaths in gulags and the Ukrainian famine, the Holodomor, were immense. It is obscene to enter any discourse in order to minimize either catastrophe. Suffering cannot be justified with a claim that someone else suffered more. Yet one can observe just such efforts from opposite ends of the political spectrum to diminish the Holocaust. Ernst Nolte famously treated the Holocaust as a response to the Bolshevik terror two decades earlier; it had, so he suggests, no significance of its own, it was merely a secondary effect. More recently, postcolonial rhetoric finds a perverse pleasure in declaring the deaths in the Shoah trivial compared to the violence of colonialism. It remains to be seen whether postcolonialism really cares about the victims of colonialism or whether it is fundamentally nothing more than the current metamorphosis of antisemitism. Neither the Noltean right nor this postcolonial left treats the genocide of European Jewry as anything except a topic to denigrate through a competition in victimhood.

Second, among the wider implications of Knabe’s text is precisely that victimhood has an appeal. The narrative around May 8 as a moment of liberation requires that Germany be viewed as having been the first victim of the Nazis. In other words, Germany must be understood as a victim in order to claim to have experienced “liberation” when the Nazis surrendered. If Germany had not been a victim, then the liberation claim makes no sense. This claim that Germany was Hitler’s first victim (and not largely a willing participant) is itself an obvious plagiarism of the founding myth of the Austrian Second Republic, according to which the annexation of Austria, the 1938 Anschluss, was Hitler’s first conquest and therefore the first act of victimization. The interesting point here is not the competition over priority—who was first, Germany or Austria—but rather the bizarre phenomenon that there is a cultural advantage declaring oneself a victim. In the German—and Austrian—contexts, inventing oneself retroactively as a victim serves the purpose of exculpation: if one was a victim, then one was never really guilty. However, the pursuit of victim identity is not just a German or Austrian monopoly; it has a wider appeal that goes well beyond Knabe’s analysis. Why is it profitable to be a victim? Why do people want to be losers?

Especially in the course of the final third of the twentieth century, a cultural shift took place across the West in which successful claims of victim status began to yield definite benefits. Such benefits could be material, in the form of positive discrimination or affirmative action. Alternatively, victimhood could bring a sort of cultural capital: we have entered a world in which it is better to be a victim than a perpetrator, better to be oppressed than an oppressor, and ultimately better to fail than to succeed, since all success is suspect and heroism consequently shunned.

Hypothetically this shift toward a victim cult might be attributed to a logic of egalitarianism that treats any inequality as evidence of exploitation rather than as a consequence of differential accomplishments or even just random luck. Defining oneself as unfairly disadvantaged maximizes the credibility of one’s claims for compensation. Victim-claiming is for grifters. For Germany as victim, the result is an evasion of guilt, but that may be a unique constellation. More broadly in advanced societies, the long-term impact of prioritizing victimhood will have other consequences, including a general suppression of merit, a reduced capacity for innovation, and failed problem-solving. A society in which merit is shunned will not be able to generate success. It will be hostile to signs of distinction, quality, and accomplishment. Decline becomes inevitable for society, even if for the individual the victim status brings advantages. Losers have their own will to power.

There is a third implication of the German embrace of “liberation” as the definition of May 8, one that is somewhat contradictory to the victimization strategy just discussed. As advantageous as it may be to claim to be a victim, there is simultaneously an indisputable appeal to reach a happy end in any narrative. That appeal is all the stronger if one can imagine oneself on the side of the victors. One way or another, a will to self-preservation seeks out opportunities for success and positive self-perception. To be sure, such a positive self-perception might in some cases just be delusional, but more generally it is part of a legitimate instinct of survival. For an individual, this survival is a matter of maturity and autonomy; for a nation, it points toward sovereignty and self-determination.

From this political point of view, the German discourse of antifascism and liberation turns out to have been particularly false. In the GDR, the narrative of liberation only served to justify the Russian occupation, and so much so that it was only with the Gorbachev reforms, decisions taken in Moscow and not in Berlin, that East Germans could begin to announce their own popular sovereignty: “wir sind das Volk.” For four decades, from 1949 to 1989, liberation in East Germany meant the lack of freedom, both for individuals and for the state.

Meanwhile the discourse of liberation in West Germany ironically only gained ground—as Knabe shows—after real sovereignty shifted away from the Allied forces to the European Union. This liberation too was ideological, if not so blatantly as during the GDR. Popular sovereignty as expressed in the Bundestag is limited by bureaucratic preferences in Brussels. That is arguably the latest chapter in the specific German history of a fraught relationship to national identity.

Yet on this matter, too, the problem is not only German, especially at this moment in world history. At stake more generally is the changing status of sovereignty. The post–World War II arrangement in which most nations, certainly in Europe, were subordinated to respective blocs, West and East, gave way to the post-1989 triumph of globalization, with extensive integration into a world market and the priority of international organizations, most prominently the United Nations. National identity and sovereignty were shunned, and especially so through the primacy of the European Union. Suddenly however the ground has shifted. That era of globalization and a “rules-based international order” appears to be coming to an end through processes of deglobalization, the erosion of international organizations, and the restructuring of international trade. A politics of transactions is replacing the primacy of deontological values. One result is the revitalization of the concepts of nation, national interest, and sovereignty, no longer disdained as “nationalistic” in an exclusively pejorative sense. Trumpism is one driver of this shift, but so are great power competition and the rise of right-wing parties in many parts of Europe. It remains an open question if a sovereigntist agenda in the countries of Europe, and not only in Germany, can successfully renegotiate the nature of the transatlantic alliance in the face of the Trump administration. Knabe’s essay is specifically about a history of political illusions in Germany—East, West, and unified. However, the questions it raises for the future concerning liberation and national sovereignty have much wider significance for the future of the West.

Topics: TPPI Translations • Reflections & Dialogues

Russell A. Berman is the Walter A. Haas Professor in the Humanities at Stanford and Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, where he directs the Working Group on the Middle East and the Islamic World. He previously served as Senior Advisor on the Policy Planning Staff of the United States Department of State and as a Commissioner on the Commission on Unalienable Rights. He is currently a member of the National Humanities Council. He is the Editor Emeritus of Telos and President of the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute.