Canada has always struck me as a country innocently surprised by its own complexity. Its seemingly polite veneer disguises a fragile federation, stitched together despite pronounced regional affinities, two official languages, vast physical breadth, and a growing number of Canadians without deep roots in this country, like me. Those who do have familial roots that go back have been encouraged to feel guilty about the manner of Canada’s creation.

These multileveled conflicts explain Canada’s existential jitters, which came suddenly to the fore when Donald Trump trolled Canada with the suggestion of turning it into the 51st state. Columnist John Ivison warned that the country is “drifting rudderless toward the falls,” while journalist Jen Gerson questioned whether Canadians have the stomach for sacrifices to maintain their sovereignty. Andrew Coyne noted that Canadians recoil from the idea of joining the United States but struggle to articulate what, precisely, holds the Canadian project together.

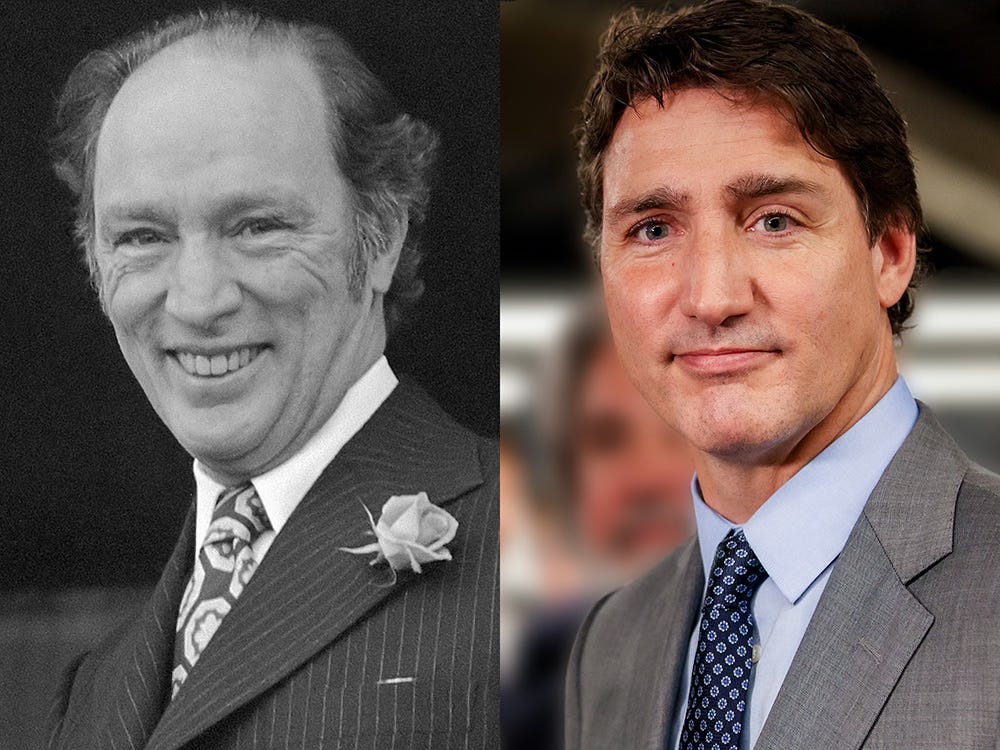

Underneath it all lies the complex truth about the impact Pierre Trudeau and his son Justin Trudeau have had on Canada—more specifically, on English Canada, the cultural locus of the deep anxiety. Neither Pierre Trudeau’s nor Justin Trudeau’s idealistic blueprints have settled Canada’s contradictions. That’s because both men, with their very different personalities, tried to leapfrog the painstaking, incremental process of forging a stable federation out of a country with not much history or a founding myth. (This does not mean that, without them, Canada would have found a surer path to a less fractured federation.)

My friend and the founder of Telos, Paul Piccone, spent much time thinking about Canada in the 1990s. He would most likely agree that both Trudeaus—unintentionally—eroded the very sovereignty they presumed to strengthen. That’s certainly what he thought of Pierre Trudeau. Piccone believed that top-down gestures such as official multiculturalism risked hollowing out Canada’s “real” cultural and political structures. Yes, inclusivity can be noble. But if it is not backed by robust local institutions and realistic policy frameworks, the confederation starts looking like a house of cards—vulnerable to sudden gusts of global upheavals.

It’s easy to imagine a future. It’s very hard to manage the day-to-day trials of unaffordable housing prices, contending with growing debt, or facing an American president who flirts with 25-percent tariffs on Canadian exports.

For much of the past century, the Liberal Party managed that complexity with a studied caution reminiscent of William Lyon Mackenzie King’s unspoken motto: “Don’t overdo things.” This oddball among Canadian prime ministers understood that a country with vast spaces and a small population—which King described as having “too much geography and not enough history”—is not one that can be easily fashioned into an ideal.

Yet every once in a while, Canada’s political steering wheel ended up in the hands of a prime minister named Trudeau determined to remake the country—first Pierre Trudeau, then his son Justin Trudeau. Different eras, different styles, but a shared ambition to reshape Canada’s very identity. Again, this primarily pertains to English Canada. And that ambition, not so ironically, edged the country toward the cul-de-sac we find ourselves in today.

When he came to power in the late sixties, Pierre Trudeau’s admirers saw a man forging a bold new destiny, one that unmoored Canada from its stodgy Loyalist traditions. As David Frum has written recently, Pierre Trudeau had “overdone things.” His attempt to transform Canada into a top-down, rationalist project—asking Canadians to forego their English and French affinities and embrace multiculturalism—proved too sweeping, too ahistorical, too dismissive of how deeply regional identities run in this country.

Nearly three decades later, Justin Trudeau arrived in office with what appeared to be an opposite approach: less austere, more empathetic, exuding emotional inclusivity and a “sunny ways” optimism. Yet beneath the difference in style lies a similar will to remake Canada in line with a personally held vision. Pierre Trudeau was the intellectual; Justin Trudeau the empath. Both believed, however, in the power of federal leadership to inspire a unified national field theory. While Pierre Trudeau recast Canada through the introduction of multiculturalism and, a decade later, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Justin Trudeau conjured a “post-national” Canada defined by moral leadership, reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, and diversity galore. In effect, father and son each tried to coax English Canada away from its older Loyalist reflexes—deference to tradition, respect for hierarchies, and incrementalism—and toward something more transformative. Hegel would describe both their strivings as emblematic of a “beautiful soul.”

In Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, the “beautiful soul” is someone who is certain of their own purity or moral stance—so certain, in fact, that they shy away from the messy realities and compromises involved in truly acting in the world. A “beautiful soul” dwells in a realm of ideals but often fails to come to terms with the friction of actual politics, material interests, or human fallibility. Both Pierre and Justin Trudeau, each in his own fashion, can be read as Hegelian “beautiful souls” in the sense that they’ve operated with visions of Canadian identity and moral progress—yet both have encountered, and sometimes sidestepped, the unavoidable complexities of governing.

There’s a similarity in that each man wanted Canada to stand for something bigger than itself. Pierre Trudeau championed rational liberalism—bilingualism, multiculturalism, and constitutional reform—that diminished the monarchy’s symbolic role. Justin Trudeau, guided by a progressive moral sensibility, centered on apologies for the inevitable historical clash between modernity and nature-bound traditions, championed diversity, and codified land acknowledgments as a version of a national anthem. In different registers, father and son attempted to transcend Canada’s inherited structures, urging us to look forward to a newly minted national ideal. But they also shared an inescapable dose of narcissism: each was so sure that his personal worldview could reorder Canada that the messy realities of confederation (Western alienation, Quebec nationalism, or lagging levels of productivity and innovation) came second to rhetorical ambitions.

Cracks appeared quickly in both projects. Pierre Trudeau’s National Energy Program stoked resentment in Alberta and beyond, damaging Western trust in Ottawa for a generation. Meanwhile, Justin Trudeau’s flurry of social reforms—laxer sentencing laws (often labeled “restorative justice”), expansive immigration targets, and turning the Canadian armed forces into a feminist project—collided with spiking criminality, opioid crises, and a housing shortage that leaves many Canadians priced out of major cities. Although the younger Trudeau did not orchestrate these policies alone, he gave them moral force. He framed them as part of a higher, more compassionate Canada, one in which old boundaries no longer apply. It was, in spirit, the same “do too much” approach that bedeviled his father.

Both father and son epitomized a drive to reimagine Canada from the top down, counting on personal charisma to smooth over complicated realities. Yes, they both championed progressive values: Pierre Trudeau with his unwavering confidence in rational liberalism, Justin Trudeau with his high-profile embrace of equity and reconciliation. But these values only carried them so far before colliding with the practical demands of a confederation that prefers its changes slow and steady.

Hence, Canada finds itself at a cul-de-sac. The “beautiful souls” in power extended the country’s horizons but also left it overstretched and unsure of the path forward. If Pierre Trudeau’s approach taught the Liberals to “never overdo things again,” Justin Trudeau’s might be repeating the same cautionary tale in a different key. Polling suggests disillusionment. The father faced a knockout defeat in 1984; the son is now stepping aside as Liberal leader under historically low approval ratings. And neither Mark Carney nor Chrystia Freeland—the two main aspirants to become leaders of the Liberal Party—has what it takes to turn Liberal fortunes around.

Maybe the question is whether we can rediscover the humbler instincts that once anchored Canadian governance. True, that cautious style can slip easily into complacency. Canada must find a way to matter in the world beyond proclaiming its desire to be good. And so we stand, suspended between paternal intellectualism and filial moralism—between the sense that we must do something big and the fear that big attempts risk fueling national breakdown.

In the end, father and son were more alike than either might have admitted: each believed his own vision could remake Canada; each ended up straining the seams of this complicated confederation. That push and pull is our Canadian cul-de-sac—a place where the hunger for grand, quick transformation collides with the reality of a country built on slow, delicate negotiations. Perhaps we’ll emerge from this impasse by learning how to keep ambition alive without ignoring the cautionary voices that whisper, “Don’t overdo things.” And maybe we’ll realize that both Trudeaus, for all their differences, have shown us the perils of skipping the hard work of forging unity one patient step at a time.

Topics: Reflections & Dialogues

Wodek Szemberg was a member of the Toronto Telos Group in the 1970s. For the next forty-odd years he was a TV producer with TVO, a provincial educational broadcaster. He is now a freelance writer and is also producing a documentary series entitled “The End of Sex”