The following essay originally appeared in German as “Wie aus Tätern Opfer wurden.” Translated and published with permission of the author from the original E-Letter 160. Translated by Konrad Berg. See also Russell A. Berman’s comments on this essay here.

These days, the Federal Republic of Germany is commemorating the end of the war eighty years ago. Politicians and the media are giving the impression that Germany too was one of the victims of National Socialism. This turns history on its head.

“The longer the Third Reich is dead, the stronger the resistance against Hitler and his ilk becomes.” This quote from journalist Johannes Gross comes to mind when one sees how Germany is commemorating the end of World War II eighty years ago. Following a series of commemorative events, the Bundestag also convened for a ceremony on May 8. Berlin even approved an additional public holiday, and a week of events with over one hundred activities took place around “Liberation Day.” One might think that Hitler’s first victim was Germany.

The exuberant commemoration stands in stark contrast to historical reality. None of the Allies had any intention of liberating the Germans in 1945. Their sole aim was to defeat them—completely—so that they would surrender unconditionally. “Now we stand before the cave from which the fascist aggressors attacked us,” Soviet Marshal Chernyakhovsky ordered his soldiers on January 12, 1945, before marching into Germany. “We will not stop until we have liquidated them. There will be no mercy—for anyone.” And on May 10, 1945, U.S. President Harry S. Truman instructed his general staff: “Germany will not be occupied for the purpose of liberation, but as a defeated enemy state.”

The Germans were also far from rushing out to cheer the Allied forces. This was due not only to the unimaginable atrocities committed by the Red Army during its invasion of the eastern territories of Germany, which drove millions of people to flee, but also to the fact that the majority of the population remained loyal to Adolf Hitler until the very end. Unlike in other countries, there were no partisan units or uprisings in Germany.

Instead, the Wehrmacht put up fierce resistance, especially on the Eastern Front. The fighting continued even after Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945. When Berlin finally surrendered on May 2, another 170,000 soldiers had lost their lives in the battle for the German capital. For historians, there is therefore no question that it was not Germany that was liberated eighty years ago, but rather Europe from the Germans.

When the Germans were finally defeated, the Allies had no intention of granting them freedom. Instead, the victorious troops occupied the entire German territory and assumed sole authority, right down to the local municipalities. “All German authorities and the German people must unconditionally comply with the demands of the Allied representatives and obey all proclamations, orders, directives, and instructions without limitation,” declared the four supreme commanders on June 5, 1945. Any political activity, even by opponents of Hitler, had to be approved by them.

For millions of Germans, the end of the war meant the exact opposite of liberation. Despite the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht, the Allies continued to take German soldiers prisoner on a large scale. Over three million were deported to the Soviet Union for forced labor, where a third of them died. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were also arrested, and almost 280,000 were sent to Soviet labor camps. In the end, the USSR annexed a quarter of the German Reich and installed a new dictatorship between the Oder and Elbe rivers.

The Allied victory meant liberation only for a minority. Around 200,000 to 300,000 people had survived imprisonment in German concentration camps and were now free. The same was true for the eight million foreign prisoners of war and forced laborers—although Stalin immediately reimprisoned those who had been abducted from the Soviet Union and sent those who were fit for work to labor camps as “traitors to the fatherland.” Deserters and opponents of the regime were also able to breathe a sigh of relief after May 8, and those who had been persecuted on racial grounds were able to leave their hiding places. The vast majority of Germans, though, were on the other side of the barricade in 1945.

Public Holiday in the GDR

However, the desire to shed the role of the perpetrator became apparent in Germany early on. At first, it was the Communists who transferred themselves from the losing side to the winning side. The founding proclamation of the KPD on June 11, 1945, written under Stalin’s watchful eye in Moscow, stated that the Red Army and its allies had brought the German people “liberation from the chains of Hitler’s slavery.” There was no mention of the fact that the KPD itself had contributed to the downfall of the Weimar Republic through its years of agitation against it.

Shortly after the founding of the GDR [the German Democratic Republic, i.e., East Germany—trans.], the SED [the Socialist Unity Party, i.e., the Communist Party that dominated the GDR—trans.] declared May 8 a public holiday. From then on, the party and state leadership gathered every year for a pompous ceremony on the “Day of the Liberation of the German People from Hitler Fascism.” Flags and banners decorated shops and office buildings, and tens of thousands marched to Soviet military cemeteries and war memorials to thank the Red Army for the liberation. On the tenth anniversary, a mass rally was even held in Berlin. The fact that a significant part of East Germany had been conquered by British and American troops went unmentioned.

The claim that the Red Army had liberated Germany soon became the most important basis for legitimizing the SED state. No one can doubt that the Soviet Union played a decisive role in defeating Hitler. Without it, the Nazi murders would have continued for a long time. On top of that, it ensured that Communists persecuted by the Nazi regime took power in East Germany. So, according to this line of reasoning, the occupiers were liberators.

In reality, the National Socialist dictatorship was merely replaced by a Communist one. The Red Army installed a vassal regime and kept it in power for decades with 500,000 soldiers. When the East Germans rose up against it on June 17, 1953, the revolt was crushed with tanks and infantry. “Liberation?” murmured people in the GDR to each other, with a view to the Soviet looting. “Yes—of watches and bicycles!”

But the term “liberation” also offered exoneration. If Germany had been liberated in 1945, then the Germans were Hitler’s victims too. And since the SED state was in a “brotherly alliance” with the Soviet Union, the East Germans were basically on the winning side. Because the GDR declared itself an “anti-fascist state” and claimed that Nazis only existed in the West, there was no longer any need to confront guilt and involvement.

Soon, the celebrations on May 8 served only to invoke the “unbreakable” friendship with the Soviet Union. Instead of thanking the liberators, the SED now sent “brotherly greetings” to Moscow, which were reciprocated in equally “brotherly” terms. The horrors of the war were only mentioned in empty phrases. To compensate for the introduction of the five-day week, the public holiday was eventually abolished in 1968.

Celebrations now had to take place without working people or in the evening. On the 30th anniversary of the end of the war, 40,000 young Communists from the GDR and the Soviet Union gathered in the dark at the Soviet memorial in Berlin’s Treptower Park to cheer on socialism with lighted torches. Later on, the SED used the date primarily to give itself a good report card. “Under the leadership of the party, the historic opportunity of May 8 was seized in the GDR,” wrote the SED central organ Neues Deutschland about the ceremony to mark the 40th anniversary of the end of the war. But then things became increasingly quiet around the German–Soviet friendship—because Kremlin leader Mikhail Gorbachev was introducing reforms that many GDR citizens wanted for their country too.

Paradigm Shift in West Germany

In the Federal Republic, developments took a somewhat opposite course. Although the victorious Western powers had already allowed free elections in their zones in 1946, leading politicians saw no reason to celebrate on May 8. If the date was even acknowledged, it was to emphasize the ambivalence of the day. “Basically, May 8, 1945, remains the most tragic and questionable paradox in history for all of us,” Theodor Heuss [the first President of West Germany—trans.] declared in the Parliamentary Council on May 8, 1949. “Why? Because we were redeemed and destroyed in one fell swoop.”

As long as many people could still personally remember the end of the war, this attitude changed little. On the 20th anniversary, Chancellor Ludwig Erhard emphasized in a radio address above all the “grace” that the Western Allies had helped the Federal Republic rebuild and welcomed it back into the family of nations. At the same time, he pointed out that the inhabitants of the GDR had not been granted such a new beginning. “Yes—if the defeat of Hitler’s Germany had wiped injustice and tyranny from the face of the earth, then the whole of humanity would have good reason to celebrate May 8 as a day of liberation. We all know how far reality is from that.”

At this time, when students were beginning to take to the streets for communism and the Federal Republic was embarking on a new Ostpolitik, a striking paradigm shift began. After the dogmatic left, it initially affected only the SPD and FDP, but later it also spread to leading CDU politicians. Now, even in the Federal Republic, it was increasingly claimed that the Germans had been liberated in 1945. In Frankfurt am Main in 1975, Bernt Engelmann, the future chairman of the German Writers’ Association, declared to 25,000 demonstrators that “the fact that the 30th anniversary of liberation is not a public holiday in this country” was proof that “fascism is once again a latent danger.” Paradoxically, the fathers and grandfathers were simultaneously accused of remaining silent about Nazi crimes or of participating in them.

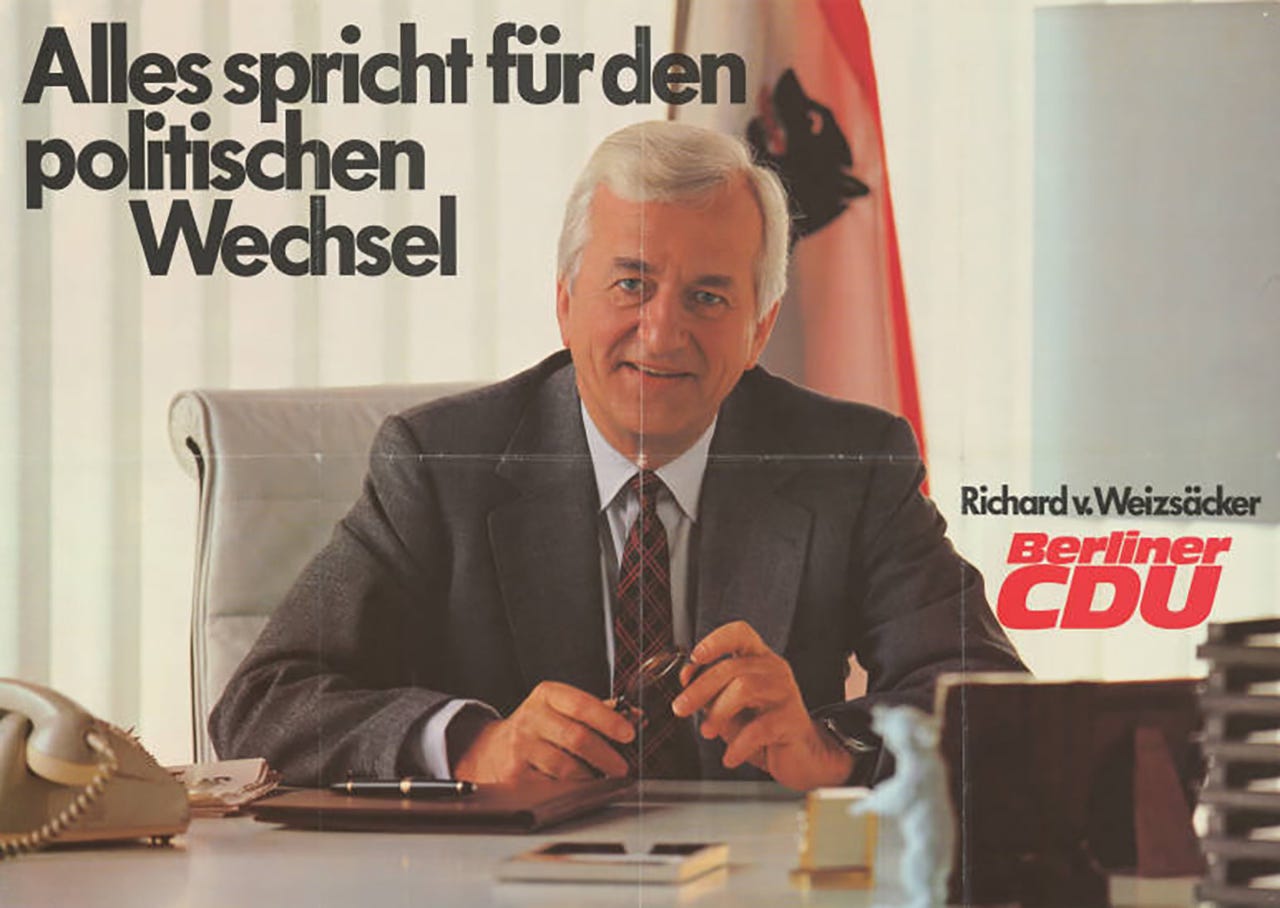

The desire to count oneself among Hitler’s victims was also reflected in the speeches of the federal presidents. In 1970, Gustav Heinemann declared in the Bundestag: “We had to endure countless dark hours before the criminal tyranny of the National Socialists was taken from us.” Five years later, his successor, Walter Scheel, used the word “liberation” for the first time when he spoke about the end of the war: “We were freed from a terrible yoke, from war, murder, servitude, and barbarism.” In 1985, Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker finally declared authoritatively: “May 8 was a day of liberation. It liberated us all from the inhuman system of National Socialist tyranny.”

Only a few people were aware that von Weizsäcker also had a personal interest in this interpretation. His father had been sentenced to seven years in prison by the Nuremberg Military Tribunal for crimes against humanity because, as a member of the Nazi Party and Hitler’s state secretary, he had signed deportation orders for French Jews to Auschwitz. As a young lawyer, von Weizsäcker had defended his father and remained convinced of his innocence. Most people had also forgotten that the CDU politician had emphasized in 1970 at a memorial service in the Bundestag that May 8 was “not a holiday for us.” Although the “aberrations and heinous crimes of National Socialism” had come to an end, “a new regime of coercion had found its way onto German soil.”

Germany as Victim

The new West German view of history increasingly ignored that the Soviet Union had done anything but liberate East Germany. Some even considered this a deserved punishment for Hitler’s crimes. It came as a surprise to the political elite when the East German population suddenly liberated itself in 1990. Because there was now a pan-German Bundestag in which East Germans were only a minority, the West German view was also transferred to Germany as a whole. This suited the deposed SED cadres just fine, as the West now also counted the Soviet Union among its liberators.

During this period, Germany underwent another role change. In 1995, Federal President Roman Herzog invited the former Allies to Berlin for the first time for a state ceremony. Together with the French president, the British prime minister, the U.S. vice president, and the Russian prime minister, they celebrated the 50th anniversary of the end of the war. The Federal Republic, like the GDR before it, had now joined the circle of victors.

In 2020, on the 75th anniversary, this type of commemoration was to be repeated on an even larger scale. German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier invited 1,600 guests from Germany and abroad to a state ceremony in front of the Reichstag, where Soviet soldiers had once hoisted the red flag. Although the event had to be canceled due to the coronavirus pandemic, politicians from the Green Party, the Free Democratic Party, and the Left Party called for May 8 to be declared a national holiday.

Again this year, Germany will not be able to show itself alongside the victorious powers. Putin’s brutal war against Ukraine would make a joint appearance appear downright cynical. And hardly anyone in Germany wants to celebrate the victory over Hitler with Trump. But some people’s regret is plain to see. “It hurts me deeply that we cannot welcome any Russians here,” said the chairman of a residents’ association in Berlin-Tempelhof, where the German capital surrendered to the Soviets on May 2, 1945, and where Berlin’s mayor, Kai Wegner, therefore laid a wreath. The municipality of Seelow and the city of Torgau also sent invitations to the Russian embassy to attend their commemorative ceremonies.

So now the Germans had to celebrate their liberation alone. Events were held in numerous cities, and an oratorio entitled “Liberation” was performed at the Berlin Academy of Arts. The media almost without exception served this narrative. On the initiative of the Left Party, May 8 is now an official memorial day in Bremen, and in almost all eastern German states. In Saxony, the CDU, for the first time, recently cast its vote in favor of a corresponding motion put forward by the Left Party. The Left Party would like to see it introduced nationwide.

What really happened in Germany on May 8, 1945, is only of interest to a few people today. What is also ignored is that the Allies still celebrate their victory over Germany on this day—not its liberation. There are hardly any people left who experienced the end of the war personally and could correct this simplistic view of history. This makes it all the easier for those born later to declare themselves liberated and thus victims of Hitler. Perhaps they should take a look at Ludwig Ehrhard’s speech, who sixty years ago recalled May 8, 1945, as follows: “It was a day as gray and bleak as so many before and after it, and so, when we heard the news of total surrender, it meant little more to us in the numbness of that time than a sigh of relief that the killing of human beings would finally come to an end.”

Dr. Hubertus Knabe is a German historian based in Berlin. He is an expert on East Germany and the legacy of communist Regimes in Europe. From 2000 to 2018 he was the Director of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial, the former central prison of the Ministry of State Security (Stasi). For more information about the author and his work, visit his website at hubertus-knabe.de.

Topics: TPPI Translations • Reflections & Dialogues